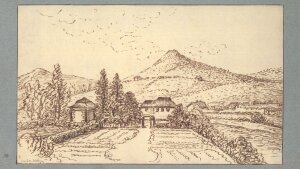

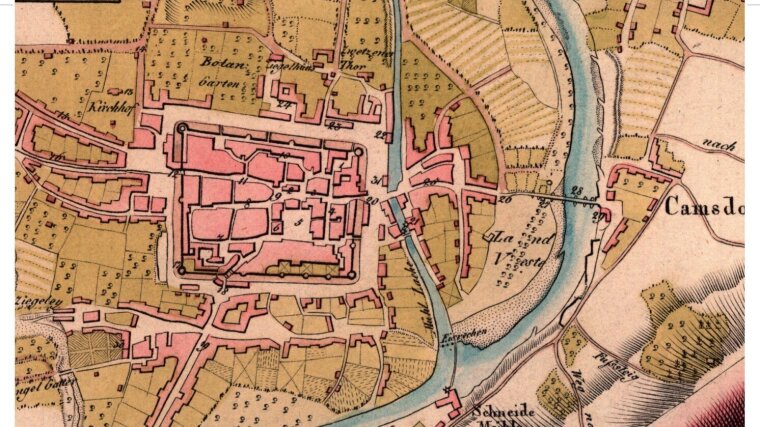

For over five decades Johann Wolfgang von Goethe has been closely connected to Jena. If one adds up his various stays from his first encounter on 23rd December 1775 to his last visit to the Botanical Garden in mid-June 1830, his presence in the city amounts to more than five years, during which Jena becomes a second home to him. As a university city, Jena forms the intellectual center of the Duchy of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach. Goethe is active here with persistence and intensity over many years: in official matters, in literary and artistic work, in science, as well as its politics. In many of these activities, natural science plays an important role. In 1784 he succeeds in the (re)discovery of the intermaxillary bone in humans. But on an institutional level Goethe gives the emerging natural sciences a new footing as well, creating a productive infrastructure for research through the establishment of collections, institutes, and professorships. In his daily and yearly chronicles, for the year 1790, two years after returning from Italy, we find the following entry:

»I rushed to resume my earlier connections to the University of Jena, which had stimulated and supported scientific endeavors. To expand, organize, and maintain the museums there, in collaboration with distinguished and knowledgeable men, was an activity both pleasant and instructive, and I felt myself to some extent compensated for the absence of artistic life through my observation of nature and the study of an all-encompassing science. The Metamorphosis of Plants was written as a relief of the heart. By having it printed, I hoped to present a specimen pro loco to those who knew. A botanical garden was in the making.«

Goethe plays a decisive role in the “Salana” becoming one of the leading universities in Germany around 1800, gaining European significance, particularly in the fields of philosophy and literature. In a letter to Karl Ludwig von Knebel in late March 1797, he gives a brief overview of the current projects of the “friends and kindred spirits” in Jena, who invite him to participate intellectually:

»Schiller is diligently working on his Wallenstein, the elder Humboldt is translating Agamemnon by Aeschylus, the elder Schlegel is working on a translation of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, and since I have every reason to reflect on the nature of the epic poem, I am at the same time prompted to turn my attention to the tragedy (Trauerspiel), through which one or the other special poetic dynamic comes to light.

In addition, the presence of the younger Humboldt, which alone would suffice to make an entire lifespan interesting, sets everything in motion that may be of interest in chemistry, physics, and physiology, so that I sometimes find it quite difficult to withdraw myself to my own matters.

If you add to this that Fichte is beginning to publish a new draft of his Wissenschaftslehre in the Philosophisches Journal, and that I, given the speculative tendency of the circle in which I live, must at least follow the matter as a whole, then you will easily see that one might at times lose track of it all, especially when plentiful dinners shorten the night and do not favor the moderation so necessary to study. I am therefore glad to return to Weimar soon in order to recover in other company. But it is incredible how great the rush of scientific activity is and at what speed the young people seize what can be acquired by them.«

The letter outlines the thinking space (Denkraum), which emerges in Jena in the late 1790s, and the creative energy and productivity that arise from this exchange between contemporaries. The maintaining of friendships is not neglected either.

»Goethe is quite different here too, it is strange to see, what influence the place has on him. In Weimar he is stiff and withdrawn. Had I not come to know him here, I would have been blind to much of him and of what is clear to me now.«,

Charlotte Schiller writes to Fritz von Stein in October 1797. Almost three years later, on 29th July 1800, Friedrich Schiller, who had by then moved to Weimar with his family in late 1799, receives a cheerful report of Goethe’s manifold and always varying occupations in the university city:

»Brief overview of the gifts that have been given to me in this city of knowledge-stacking and science for entertainment as well as for spiritual and bodily nourishment:

Loder gave

excellent crayfish, of which I wished you had a plate,

delicious wines,

a foot to be amputated,

a nasal polyp,

several anatomical and surgical essays,

various anecdotes,

a microscope and newspapers.

Frommann

Gries’s Tasso,

first issue of Tieck’s journal.

Fr. Schlegel

a poem by him,

printer’s sheets of the Athenäum.

Lenz

new minerals, especially very beautifully crystallized chalcedonies.

Mineralogical Society:

several essays of high and low standing, occasion for all sorts of reflections.

Ilgen

the story of Tobias,

various cheerful philologica.

The botanical gardener

many plants arranged according to the orders in which they bloom here in the garden.

Cotta

Philibert’s Botany.

Chance

Brentano’s Gustav Wasa.

The literary quarrels

wish to read Steffens’s little treatise on mineralogy.

Count Veltheim

his collected writings, spirited and witty; but unfortunately frivolous, dilettante, at times cowardly

and fantasizing.

Some business

occasion to amuse and to annoy myself.

[…]

If you now let all these spectres haunt about together, you can imagine that I am never alone, neither in my room nor on my solitary walks. For the coming days I am promised yet more curious variety, of which I will send more with the next messenger. At the same time, I shall be able to tell you the day of my return. Be well and active, if this barometric high agrees with you as well as it does with me.«

The appended chronicle of Jena’s »gifts« may illustrate how Goethe’s multilayered, continuous, and highly mobile commitment to the university city over the course of his life unfolds into a radiant arc, that connects Weimar and Jena with one another:

»Always searched, always founded, / Never closed, often rounded.«

(»Stets geforscht und stets gegründet, /Nie geschlossen, oft geründet.«)

(Wide world and broad life, Jena 1817)