An invaluable source of support for Goethe’s scientific studies was the University of Jena. Located just 23 kilometers east of the ducal residence in Weimar, it offered a vibrant academic environment that allowed Goethe to consult knowledgeable experts at any time and to access the collections on geology, mineralogy, and zoology. To be able to pursue his scientific studies undisturbed, he often spent several weeks in Jena, initially residing in the wing of the old city palace, which also housed the collections. He himself contributed significantly to the steady expansion of the university’s collections and actively advocated for the recruitment of capable lecturers.

Another place Goethe frequently visited in Jena was the Botanical Garden, where he lived in the inspector’s house from the summer of 1817 onward. Here he was able to exchange ideas with August Johann Georg Karl Batsch (1761–1802), who had been appointed the garden’s first director in 1794. Goethe also discussed botanical topics and methods with Batsch’s successors, Franz Joseph Schelver (1778–1832) and Friedrich Siegmund Voigt (1781–1850); all three naturalists adopted the concept of the metamorphosis of plants as a guiding principle for their work.

Skull of a rodent, after a sketch by Goethe

Picture: Klassik Stiftung WeimarThe Jena professors Justus Christian Loder (1753-1832) and Johann Georg Lenz (1748-1832) were also important discussion partners for Goethe: Under Loder’s guidance, he deepened his knowledge of anatomy; their joint investigations led to the discovery of the intermaxillary bone in humans in 1784. Lenz was curator of the collections for mineralogy and geology and founder of the “Mineralogical Society” in Jena, later also becoming a mining councilor and professor. As the keeper of the geological cabinet, he expanded the collections with great enthusiasm.

In coordination with Johann Friedrich August Göttling (1755-1809), Goethe advanced the field of chemistry at the University by establishing the first chair (1789). As government minister, he took charge of setting up a chemical laboratory. Göttling's successor was Johann Wolfgang Döbereiner (1780-1849). With him Goethe maintained a lively exchange, in person and in written correspondence.

Jena and the natural sciences also marked the beginning of Goethe's friendship with Friedrich Schiller (1759-1805). Their famous discussion about the “symbolic plant” led to a closer bond between the two poets. Goethe later recorded this event in his text Glückliches Ereignis. There is a letter from Schiller dated November 21, 1794, in which he writes the following about Goethe: "He is a most interesting character in every respect, and his sphere is remarkably broad. In matters of natural history, he is excellently versed and he possesses a breadth of vision that casts a splendid light on the economy of the organic body.”

In Jena, Goethe also met the philosophers Johann Gottlieb Fichte (1762-1814), Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling (1775-1854) and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770-1831). His complex discussions and productive interactions with these thinkers provided important impulses for his investigations into nature and, conversely, his theory of metamorphosis was intensively received by Schelling and Hegel [see Förster 2022]. Fichte's Wissenschaftslehre (1794) strengthens Goethe's belief that polarity is fundamental to all phenomena. Together with Schelling, he studies his First Outline of a System of the Philosophy of Nature (Erster Entwurf eines Systems der Naturphilosophie, 1799). However, Goethe was never to become too immersed in the speculative part of philosophy of nature – for that, his orientation towards precise observation was too strongly developed. On the path to his Phenomenology of Spirit (Phänomenologie des Geistes, 1807) Hegel later asks, with reference to Goethe, how consciousness and organic life can be distinguished from one another.

Oblique and horizontal rock formations, sketches by Goethe

Picture: Germanisches Nationalmuseum NürnbergWilhelm von Humboldt (1767-1835) and Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859) had already come to Jena in 1794. During this time, Goethe maintained a lively exchange with both brothers about the method of natural history. He would follow Alexander's travels with admiration; his geological hypotheses, however, could no longer be approved by the old Goethe. The contact with Wilhelm, on the other hand, lasted a lifetime.

From 1809, or officially from 1815, Goethe held the “overall supervision of the immediate institutions for sciences and art in Weimar and Jena” and was therefore responsible for the orderly running of the university. The staff of the academic institution, with around 2000 students at that time, were at his service: the gardeners, custodians and assistants implemented his suggestions and ideas, supplied him with materials and took care of his assignments.

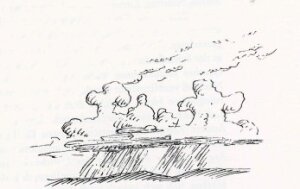

Stratus cloud layer with superimposed cumulus clouds, pen drawing by Goethe, pen and ink drawing by Goethe

Picture: Klassik Stiftung WeimarFrom 1811, a network of meteorological measuring stations was set up in the duchy at Carl August's behest. The newly built observatory in Jena – it was attached to Schiller's former garden house – served as its central institution; it was initially directed by the astronomer Karl Dietrich von Münchow (1778-1836), and from 1819 by Johannes Friedrich Posselt (1794-1823). The observatory supplied Goethe with astronomical and meteorological data, statistical records, and weather observations, to which he devoted increasing attention in later years. After Posselt's death in 1823, Ludwig Schrön (1799-1875) assumed the direction of the observatory, thereby having the chance to publish in Goethe's booklets Zur Naturwissenschaft.

However, things were not without discord in the academic world. Goethe never came to terms with the physician Lorenz Oken (1779-1851), who had been teaching in Jena from 1807. They disagreed on the vertebral theory of the skull. As one of the leading figures of romantic philosophy of nature, Oken was the editor of the journal Isis; political differences ultimately led to his departure from Jena in 1819.

(Margrit Wyder, forthcoming in: „Bewegliche Ordnung”. Goethes Naturforschung, ed. by Helmut Hühn and Margrit Wyder. Göttingen, 2025).